Ruthless Endangerment

Editors note: This post is especially relevant for the statement:

Like Large Language Models, driving automation is a technology that draws us into a fantasy, thinking a vehicle “can drive itself” after a few minutes of plausible performance. Tesla’s Elon Musk and Uber’s Travis Kalanick (among others), were enormously successful at monetizing the performance of self-driving without ever coming close to doing the thing that actually makes a system “self-driving”: taking legal liability for it.

Original article by E.W. Niedermeyer from Niedermeyer.io

Last Friday, Rafaela Vasquez pled guilty to Endangerment in Maricopa County Court, agreeing to three years of supervised probation. The plea ends an ordeal that began five years ago, around 10 pm on March 18, 2018, when the Uber prototype self-driving vehicle Vasquez was supervising struck and killed a pedestrian, Elaine Herzberg, on a darkened street in Tempe, Arizona. Though the crash grabbed headlines for being the first fatality involving an autonomous vehicle, Vasquez was initially charged with negligent homicide (facing up to 8 years in prison), while Uber faced no criminal charges at all.

Despite being one of the most fascinating and important stories in emerging technology, the Vasquez case remains wildly undercovered. WIRED has the definitive piece so far and it’s a cracker, definitely read it, but somehow the public still doesn’t appreciate what a SciFi horrorshow the first fatal robotic car crash really is. Probably because the whole thing turns on some basic facts about the technology that the public doesn’t seem ready for.

Most coverage of the story plays up the crash as “stirring up philosophical questions about responsibility for autonomous vehicles,” trying to tap into the oddly popular desire for life to resemble an Asimov book, but the question doesn’t actually turn on philosophy at all. In the science fact dystopia we actually inhabit the disasters aren’t caused by misprogrammed robots, but by humans doing predictably human things with predictably human results.

To understand what happened that night in Tempe, you first have to understand Uber and its “Advanced Technologies Group.” A blitzscaling venture capital fameball of unprecedented proportions, Spooked by the prospect of a Google monopoly on self-driving vehicle technology, Uber CEO Travis Kalanick hired away notorious hard-charger Anthony Levandowski and ransacked Carnegie Mellon’s famed robotics department to build ATG. In addition to what was later deemed stolen lidar technology, Levandowski brought a move-fast and break-things attitude to AV development that quickly ran afoul of California’s regulators.

Uber found a far more lenient regulatory environment in Arizona, where it proceeded to rack up test miles as quickly and cheaply as possible. Uber hired contractors like Vasquez, who had previously worked in online content moderation, gave them minimal training, and then left them by themselves to monitor autonomous vehicles for long nighttime shifts. The subsequent NTSB report found that ATG had no formal safety plan, standardized operations procedures, or a fatigue risk management policy for operators. Uber was setting up Vasquez for failure, along with every other safety operator in its fleet.

Three years earlier, the Society of Automotive Engineers established a set of guidelines for precisely the kind of testing Uber was engaged in, recommending extensive training (classroom, simulator, track and public roads), workload management protocols, and other measures to avoid automation fatigue and distraction. After all, psychologists have understood for more than a century that humans are unable to maintain attention for long if a task is too repetitive and boring. Any one of us, no matter our moral character or skill as a driver, will become inattentive and complacent after long periods of boring, low arousal monitoring. The NTSB found that Rafaela Vasquez had ridden the exact same route 73 times in autonomous mode, during shifts running from 8 pm to 3 am.

The technical failures of the Uber ATG system are interesting, but almost of no consequence; this was a prototype, not a fully vetted production system, so failure of some kind was inevitable. That’s precisely why Vasquez was there: because everyone involved knew something would go wrong at some point. But Uber didn’t equip or support Vasquez to actually prevent a crash or death when their technology failed, as their total failure to equip her with the training, partner, and workload management she needed proves. They simply wanted her there as a scapegoat, or as Madeleine Clare Elish put it in her excellent 2019 paper, a Moral Crumple Zone.

This was made even more clear when Tempe police released video revealing Vazquez looking at a smartphone moments before the crash, accompanied by a smug statement from Uber blaming Vasquez entirely. The fact that released video also showed police telling Uber representatives that they would be “working together,” and that Maricopa County prosecutors had to refer the investigation to another county because of cozy relations with the company, round out the picture. Given that nobody reading or commenting on the story is likely to find themselves in her position, especially now that Uber’s ATG has been unceremoniously sold off, makes it all the easier for the public to blame a woman whose job put her in an impossible situation, with life and death consequences.

Except that many more of us might well find ourselves in a similar situation. Earlier this year, a Tesla driver named Kevin Riad was convicted on two counts of vehicular manslaughter and put on probation, for a crash that occurred when his vehicle exited a freeway in Autopilot mode and ran a red light. Unlike Vasquez, who was employed to test a prototype autonomous vehicle and insufficiently supported by a weak safety culture, Riad simply bought a car with a clear liability disclaimer. Still, we know that overstating the capability of systems like Autopilot (as Elon Musk so often does) contributes to inattention by users as well, by miscalibrating user trust in a process called Autonowashing.

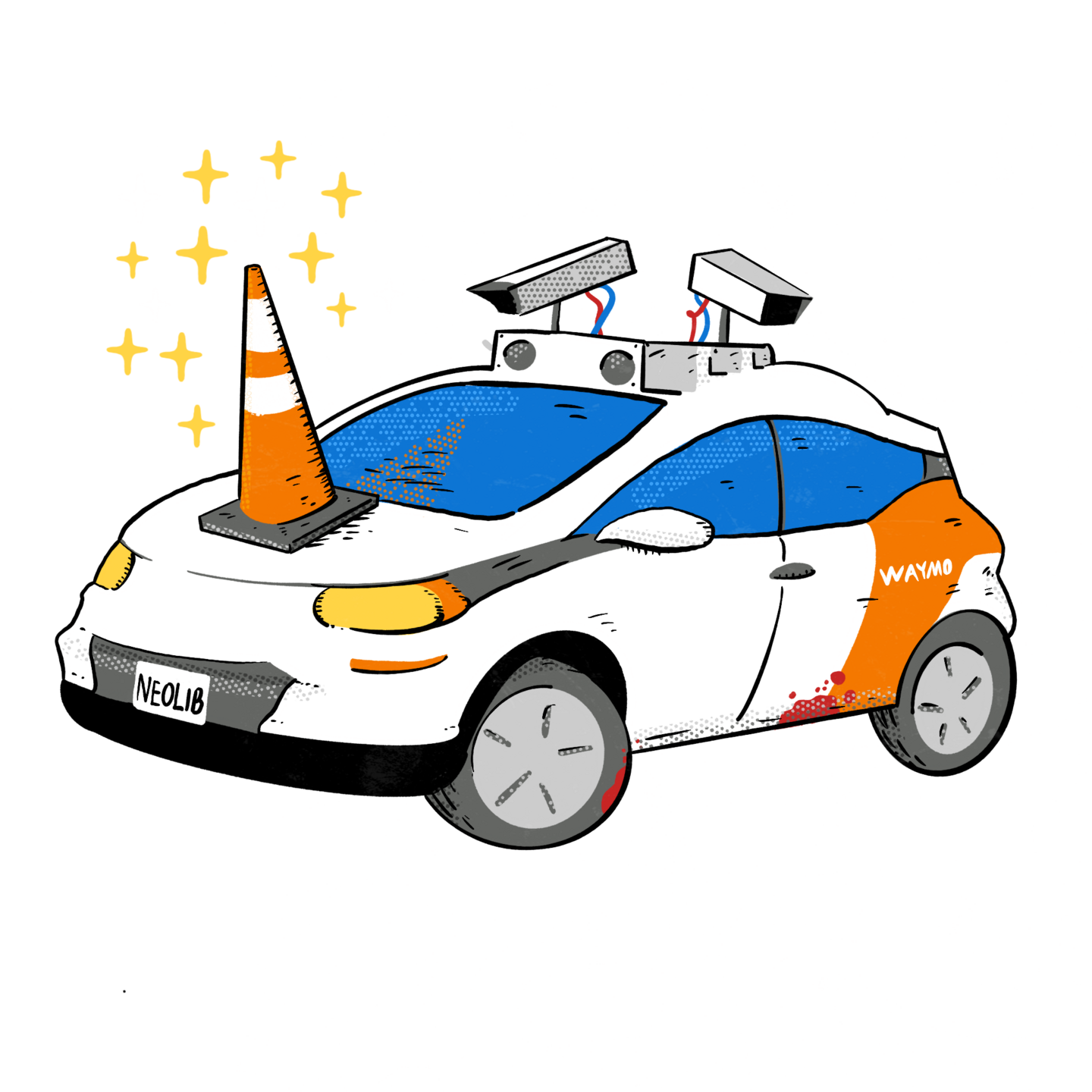

Like Large Language Models, driving automation is a technology that draws us into a fantasy, thinking a vehicle “can drive itself” after a few minutes of plausible performance. Tesla’s Elon Musk and Uber’s Travis Kalanick (among others), were enormously successful at monetizing the performance of self-driving without ever coming close to doing the thing that actually makes a system “self-driving”: taking legal liability for it. Thanks to Vasquez and Riad, and likely many more to come given the precedents that have been set, they don’t have to.

There are massive differences between the Vasquez and Riad case, but both illustrate a terrifying new risk on public roads. Not robocars run amok, or making disturbing trolley-problem choices, but systems that are just good enough to fool us into trusting our lives, and those of everyone else on the road, to them, but whose makers won’t take responsibility for them when they fail. We are told that automation always makes driving safer… and as long as the Teslas and Ubers of the world can stick their customers and employees with the blame when their technology fails, it will always be true.