The Atlantic – San Francisco Has a Problem With Robotaxis

See full original article in the Atlantic by David Zipper.

A century ago, cities surrendered to the gasoline-powered car. Will they do the same for autonomous vehicles?

A few weeks ago, Dan Afergan, a software engineer, met a few friends at 540 Rogues, a bar in San Francisco’s Inner Richmond neighborhood. As Afergan and his companions nursed their drinks, someone walked in with some unusual news: “There’s a Cruise out there with a cone stuck on it.”

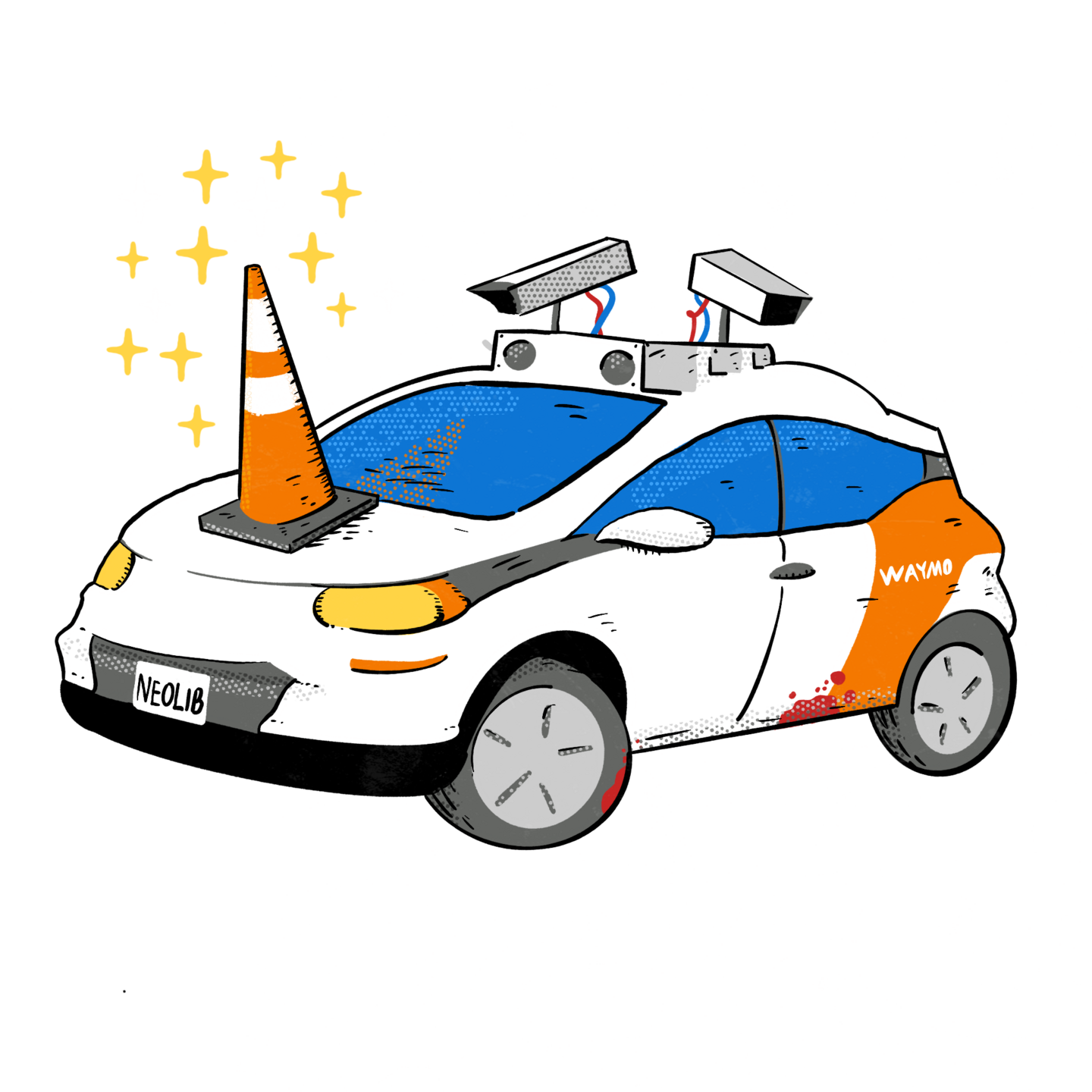

Afergan stepped outside to check it out. Sure enough, a self-driving cab from the company Cruise, which is majority-owned by General Motors, stood frozen in the middle of the street, its hazard lights blinking. A bright-orange cone was perched on the robotaxi’s hood.

“At the time, I thought it was a dumb prank,” Afergan told me later. “But one friend said, ‘No, I’ve heard about this.’ Until then I didn’t know that there are a bunch of people who are anti–autonomous vehicles.”

Read: Seven arguments against the autonomous-vehicle utopia

The “coning” that Afergan witnessed was part of a campaign launched by Safe Street Rebel, a local activist group previously known for organizing protests in support of bike-lane construction and public-transit funding. Now its members have turned their attention to robotaxis. According to government data reported by the news site Mission Local, Cruise and its rival Waymo—a subsidiary of Google’s parent, Alphabet—together operate 571 self-driving cabs in California. Users can hail them via an app. Service is concentrated in San Francisco, where the companies have been subject to a variety of limits imposed by the California Public Utilities Commission. The two companies now want the CPUC to remove those restrictions, despite objections from San Francisco’s police union and transportation and fire departments about robotaxis’ troubling habit of blocking traffic and obstructing emergency vehicles. The commission has postponed a decision twice but is expected to vote tomorrow.

After realizing that placing a simple orange cone on the hood seemed to paralyze a state-of-the-art autonomous vehicle, Safe Street Rebel posted a TikTok video encouraging San Francisco residents to try it for themselves. hell no. we do not consent to this, a caption declares over a clip of a robotaxi on a city street. As the video ricocheted across social media, Cruise and Waymo were unamused, threatening to call the cops on anyone who placed a cone on their cars.

One might dismiss the guerrilla-style coning of robotaxis as one more sign of an anti-tech backlash, or just of San Francisco being San Francisco. But those narratives understate the significance of the current uproar. For the first time, urban residents, tech companies, and public officials are debating whether and how self-driving cars fit into a dense city. This is a conversation that needs to happen now, while autonomous-vehicle technology is still under development—and before it reshapes life in San Francisco and throughout urban America. A century ago, the U.S. began rearranging its cities to accommodate the most futuristic vehicles of the era, privately owned automobiles—making decisions that have undermined urban life ever since. Robotaxis could prove equally transformative, which makes proceeding with caution all the more necessary.

in the utopian version of the robotaxi story, trips in autonomous electric vehicles become so affordable, easy, and pleasant that many people decide to forgo owning their own car. Because San Francisco is close to Silicon Valley and is home to so many investors and tech journalists, the city is a high-profile, high-stakes testing ground for the emergent technology. It’s also a more challenging environment for autonomous cars than sprawling places such as Phoenix and Las Vegas, which have fewer pedestrians, cyclists, and transit riders.

The novelty of self-driving cars is a key part of their appeal. “Tourists take pictures of me, so I get to feel like a small celebrity,” a San Francisco resident named David Anderson, who says he requests a Waymo ride multiple times a week, told me. Beyond the wow factor, these companies offer a service akin to ride-hailing, which researchers have found worsens urban congestion and pulls riders away from transit.

Perhaps the most appealing argument for robotaxis and other self-driving vehicles is that human drivers are so fallible. Last month, a Waymo co-CEO published an op-ed in the San Francisco Chronicle extolling the safety of the company’s vehicles, and Cruise ran a full-page ad in The New York Times and other newspapers presenting its technology as a solution for the 42,795 road deaths last year in the United States. (The companies have been reluctant to share data on their operations, hampering unaffiliated researchers who might weigh in objectively.) For now, though, robotaxis are creating a slew of headaches for San Francisco officials. Even with limited deployment, the vehicles have blocked traffic lanes, obstructed buses and streetcars, driven over a fire hose, and entered an active construction zone. Since June 2022, San Francisco logged almost 600 instances in which robotaxis made unplanned stops—some lasting hours—on public streets. That count was limited to incidents reported to city officials, suggesting that the actual number could be far higher.

Read: Finally, the self-driving car

“These vehicles perform very well in basic suburban driving conditions, but they face challenges when cities have greater levels of complexity, and particularly when they are in unexpected situations,” Jeffrey Tumlin, the head of San Francisco’s Municipal Transportation Agency, told me. “In a city like San Francisco, the unexpected is ubiquitous.” Jeanine Nicholson, the city’s fire chief, offered a blunter robotaxi assessment: “They’re not ready for prime time.” Steven Shladover, a research engineer at UC Berkeley who has advised California officials about autonomous vehicles, told me that Cruise and Waymo vehicles sometimes show admirable sophistication. But, he said, “you’ll almost inevitably encounter a situation where the vehicle will act like an inexperienced driver. It’s an adolescent, not yet an adult.”

Cruise and Waymo have responded to critics by touting their vehicles’ overall safety record, which they argue is far superior to human drivers’. “We should be doing everything possible to quickly and safely scale this technology and combat a horrific status quo,” Cruise declared in a statement last month, after CPUC postponed its decision on easing limits on robotaxis. “Every single day of delay in deploying this [life]-saving autonomous driving technology has critical impacts on road safety,” Waymo asserted.

Robotaxi companies are under pressure to scale up quickly. Having invested billions of dollars, their backers want to see growth (the demise last year of Argo AI, a prominent robotaxi competitor backed by Ford and Volkswagen, undermined investor confidence in the industry). Cruise is aiming to put 1 million robotaxis on U.S. streets by around 2030, and CEO Kyle Vogt saidduring an earnings call last month that “certainly there is the capacity to absorb several thousand [robotaxis] per city at a minimum.” (When I requested comment from Cruise by email, the company did not respond to my questions about its expansion goals.) Any delay from the CPUC—one of whose five members is Cruise’s former managing counsel—makes the company’s objectives harder to achieve.

Despite its current challenges, self-driving technology is steadily improving, inferring new lessons from reams of data collected from vehicles plying public streets. Eventually, robotaxis might avoid the kinds of traffic and safety hazards that have afflicted San Francisco. But even if robotaxis operate perfectly, what would life be like in a city where they are ubiquitous?

Before gas-powered automobiles arrived en masse, American streets bustled with activity. Pedestrians, horse-drawn carriages, and bicyclists jostled for space, and children played stickball, marbles, and other games on the pavement. Streetcars carried millions of passengers on 45,000 miles of track; in the 1920s, most of Chicago’s nearly 100 streetcar lines operated 24 hours a day, with some providing service at eight-to-10-minute intervals in the dead of night. Photographs of urban thoroughfares at the dawn of the 20th century may appear chaotic, but the danger was limited, because no one traveled much faster than 15 miles per hour.

Early on, cars were too pricey for all but the most affluent urban residents. But after the introduction of the Ford Model T, U.S. car sales surged, rising from 181,000 in 1910 to 4.5 million in 1929. Traveling faster than anything else on the street, these vehicles soon presented a mortal threat to pedestrians and children. Some 25,800 people died in crashes in 1927, a per-capita fatality rate substantially higher than today’s despite Americans owning far fewer cars at the time. “The dead were city people, they were not in motor vehicles, and they were young,” the University of Virginia historian Peter Norton wrote in Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City.

Read: Everyone has ‘car brain’

In the early 1920s, Norton recounts in his book, St. Louis and Pittsburgh residents erected immense memorials to those killed in car crashes. In Cincinnati, a 1923 ballot initiative proposed a mandate that all motor vehicles within the city be outfitted with speed governors set to 25 miles per hour. “Forty-two thousand people put their names on petitions, just in that city,” Norton told me. “That’s a sign that there were a lot of people troubled by car domination.” Alarmed, the auto industry rushed to mobilize against the Cincinnati measure, which was defeated.

Seeking to avoid debating whether fast vehicles could coexist with urban neighborhoods, the car industry worked with friendly government officials to reframe road safety as the responsibility of the individuals at risk of being struck. Car groups funded school curricula instructing children to stay out of streets and worked to establish jaywalking as a crime. Meanwhile, city sidewalks and public spaces were torn up to expand traffic lanes.

Urban cars proved devastating for streetcars unable to navigate around a motor vehicle blocking their tracks. “The arrival of private automobiles quickly gummed up streetcar efficiency and made them much less competitive and comfortable,” Nicholas Bloom, a Hunter College urban historian and the author of The Great American Transit Disaster: A Century of Austerity, Auto-Centric Planning, and White Flight, told me in an email. “Streetcars lacked exclusive rights of way, so exploding auto traffic dramatically slowed streetcar service.” Automobiles also enabled many city residents to relocate to suburbs unreachable by transit. By the 1950s, American streetcar service had collapsed. In 1960, just 12 percent of commutes to work occurred on transit; by 2019, the share had tumbled to 5 percent.

The aftermath of these early auto-centric decisions still reverberates today, causing cities to become dirtier, more dangerous, and less fun. More than half of the land in many downtowns is used to move and store motor vehicles, occupying space that could otherwise accommodate housing, retail, playgrounds, and parks.

Many cities are now taking steps to correct past mistakes. Last year, Denver voters passed a referendum that will allocate millions of dollars to improve sidewalks. Striving to make public transportation competitive with car trips, Phoenix and Madison, Wisconsin, are planning their first bus-rapid-transit lines. (Such moves could have aided streetcars a century ago.) In recent years, California, Nevada, and Virginia have moved to decriminalize jaywalking. Progress is gradual, but it is real.

Autonomous vehicles threaten that momentum, for the simple reason that self-driving cars are still cars. Whether operated by a human or software, automobiles generate pollution, require traffic lanes, and endanger pedestrians and cyclists.

One member of Safe Street Rebel told me he agreed with AV boosters that self-driving cars could make car trips easier than ever—which is exactly the problem (he asked to remain anonymous because of the dubious legality of the group’s activities). “We have these two competing visions for the future of transportation,” he said. “We’re now talking about tearing down sections of freeways in San Francisco, but AVs go completely against that, because they need that road space to go quickly. If we have more AVs, do we have to keep those freeways? Or can we invest in better transit, so we don’t need those freeways?”

Joshua Sharpe: We should all be more afraid of driving

Norton, the University of Virginia historian, thinks the San Francisco activist’s concerns are valid. “Once we have streets with robotaxis, there is definitely a risk that the city feels that it doesn’t have to supply basic public transportation,” he told me. In fact, such views have already been shared. “Don’t build a light rail system now. Please, please, please, please don’t,” Frank Chen, a partner at the venture-capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, told The New York Times in 2018. “We don’t understand the economics of self-driving cars because we haven’t experienced them yet. Let’s see how it plays out.” The year before, officials in Miami-Dade County, Florida, cited autonomous vehicles as a reason to refrain from expanding public transportation.

But any suggestion that the vehicles will significantly improve mobility on their own seems fanciful. A few years ago, researchers provided 13 Bay Area volunteers with a personal chauffeur who would bring them wherever they liked, mimicking the experience of accessing a self-driving car. During their week with the chauffeur, the test subjects traveled a whopping 83 percent more car miles than they did previously. Autonomous vehicles would be an environmental disaster if they induced anywhere near that much extra driving. They could also create unprecedented gridlock on highways and streets.

Shladover, the Berkeley research engineer, thinks such fears are overblown. “It depends on how the self-driving cars are used,” he said. “If they are deployed in ways that are complementary to transit, such as serving parts of the city that have minimal transit access, that is a significant plus.” But would for-profit companies focus on so-called transit deserts, or would they cater to the needs of a smaller subset of wealthier customers? For AVs to complement transit lines, urban residents must be willing to hop into robotaxis with strangers. That assumption is built into Cruise’s small, podlike Origin shuttle vehicle, but the troubles of Uber Pool and Lyft Line cast doubt on the idea.

Even if AVs do live up to their hype technologically, their long-term effect on cities is hard to predict. “While there’s a lot of data indicating that AVs can contribute to overall safer streets, the reality is that they exist in a transportation ecosystem and are not a panacea,” Drew Pusateri, a Cruise spokesperson, told me in an email. “We need a much broader approach to road safety that includes more investments in mass transit, wider, slower roads and a variety of other solutions.” But the past century suggests that when a transportation system is built primarily for cars, people using other modes get short shrift. That may remain true even when the cars are driving themselves.

In San Francisco, public officials and activists are raising fundamental questions about the desirability of autonomous vehicles within cities—questions that have seldom been aired in public. Instead, elected officials seeking an aura of innovation in states such as Texas and Arizona have actively pursued early AV deployments, minimizing regulations and shunning hard questions. Only now, in California, are robotaxi companies finding themselves in the unfamiliar position of playing defense in the public arena.

Regulators at the CPUC and elsewhere should encourage a vibrant public dialogue around autonomous vehicles, and learn from it. The worst thing they can do is rush decisions to scale an alluring new technology whose downsides could be catastrophic.