SF Chronicle – Robotaxis are good for disabled people, advocates say. But are wheelchair users being thrown under the (autonomous) bus?

See full original article in the SF Chronicle by Soleil Ho.

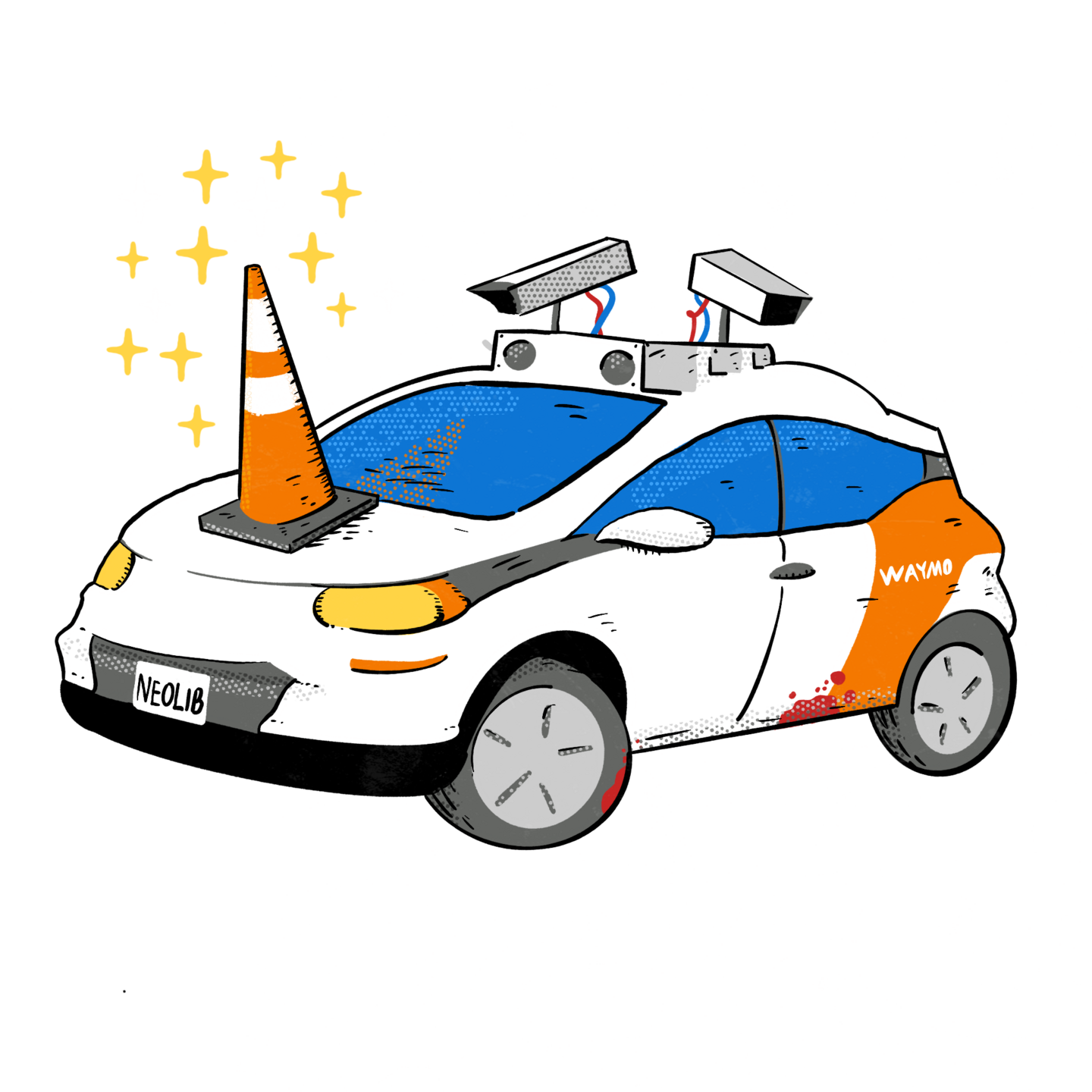

At Thursday’s meeting of the California Public Utilities Commission to decide the future of driverless cars in San Francisco, a theme emerged during the lengthy public comment period. Many of Cruise and Waymo’s proponents argued that driverless carswould be transformative for disabled people. Others accused the companies, and the commission, of throwing disabled people under the figurative bus.

Driverless cars represent independence and freedom, said several self-described disabled people, including representatives of organizations partnering with Waymo. A driverless car won’t reject a service dog, said one; it’s safer for neurodivergent people to use, said another.

On the other hand, a woman in a mobility scooter said that she’d had multiple close calls in crosswalks with driverless cars that didn’t seem to see her. Others, including some taxi drivers and members of the Paratransit Coordinating Council, wondered how a driverless car would assist a person in a wheelchair with getting inside of the vehicle.

If you take every stakeholder at their word, this seems to be a case of overflowing good intentions that happen to take opposing sides. But after speaking with several transit experts and members of the disability community, I found many reasons to be skeptical that the disability rights angle is more than just window dressing for the pursuit of profit.

The industry’s public relations campaign has put a lot of effort into drawing a connection between disability rights and driverless cars. Driverless cars “reshape the transportation landscape for people with disabilities,” Waymo claims. The company’s blog features interviews and videos of ride-alongs with members of disability organizations like the LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired in San Francisco.

I’m sure this is unrelated to the fact that LightHouse’s CEO, Sharon Giovinazzo, testified in favor of the expansion at multiple commission meetings. Safer Roads for All, a campaign created and funded by the Autonomous Vehicle Association and Waymo, also took care to highlight disability advocacy in its coverage of Thursday’s meeting.

Anna Zivarts, a disability rights and transit advocate based in Washington state, told me that Cruise has reached out to her already for support — potentially for an expansion effort there. “They are trying really hard to engage with the disability community right now,” she said, but she says the apparent benefits are halfway measures that pit the different needs of community members against each other.

The problem is that driverless cars’ transformative potential for disabled people is, at the moment, just potential. And disability advocates are all too used to having their concerns shifted to the backburner when it comes to new technologies.

Ian Smith, an engineering manager who lives in Oakland, told me that wheelchair users like them had to fight for equitable access to transportation when Uber and Lyft came onto the scene.

At the meeting, Smith was optimistic but urged the commission to vote against the resolutions: “I see a lot of potential in this tech for the disability community. But my concern is that we don’t have an agreement on what accessibility looks like for these vehicles.”

If you don’t use a wheelchair, sure, you can go all-in on driverless cars. (Currently, neither Waymo nor Cruise offer autonomous wheelchair-accessible vehicles, though Cruise is developing one.)

“Why did the Lighthouse for the Blind say they’re in favor when actually there are numerous issues with accessibility?” asked Michael Smith, a disability activist and transit advocate. “They’re throwing people in wheelchairs under the bus by saying that the (driverless cars) are accessible when they’re not. People with disabilities need to work together — it’s tough enough to make things work.”

Not only are wheelchair users excluded from these services, but there’s doubt that these vehicles can handle people who aren’t even trying to have anything to do with them. A recent briefing on algorithmic bias from the Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund found that ableism could easily become a part of training data. If a system is only trained on people who can walk — then those who don’t fit that moldcould easily go unrecognized.

The driverless car question also divides disabled people of different means. According to census data, disabled Americans are twice as likely to live in poverty as their nondisabled peers, and there’s no guarantee that driverless car technology will be more financially accessible than public transit or taxi paratransit.

In fact, the expansion may reduce the availability of affordable transportation services for disabled people if it repeats the impact of Uber and Lyft. A 2019 San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency study found that as ride-hail services increased, the number of taxis decreased. But it wasn’t a one-to-one swap; as taxi service declined, so did vehicles with wheelchair ramps.

At an earlier meeting, the Public Utilities Commission declined to set rules for accessibility in driverless vehicles, let alone a process for the enforcement.

“I would love for us to get to a world where that is part of good planning but I can’t trust that in good faith,” Ian Smith said. “From day one, these services should be accessible — not 10 years later.”

Without regulation, all it could take for the good-faith steps these companies have taken toward accessibility to retreat is a dip in share prices or a change in leadership, factors that are all too common in the tech world.

Driverless car companies might say they care about disability access. But until there’s actual muscle behind those efforts, it’s just empty words