Self-driving cars still aren’t the future

Editors note: The full original post is by Paris Marx and is from his blog on technology disconnect.blog . We highly recommend visiting and subscribing to disconnect.blog to learn more about the perils of technology.

A Cruise disaster deflates the robotaxi hype once again

Since March 2018, when an Uber test vehicle killed a pedestrian in Arizona, there’s been a notable chill on the future of self-driving vehicles. Even Elon Musk’s claim that Tesla would have a million robotaxis on the road by the end of 2020 wasn’t enough to really move the needle — probably because most people knew it was complete bullshit the moment it escaped his lips.

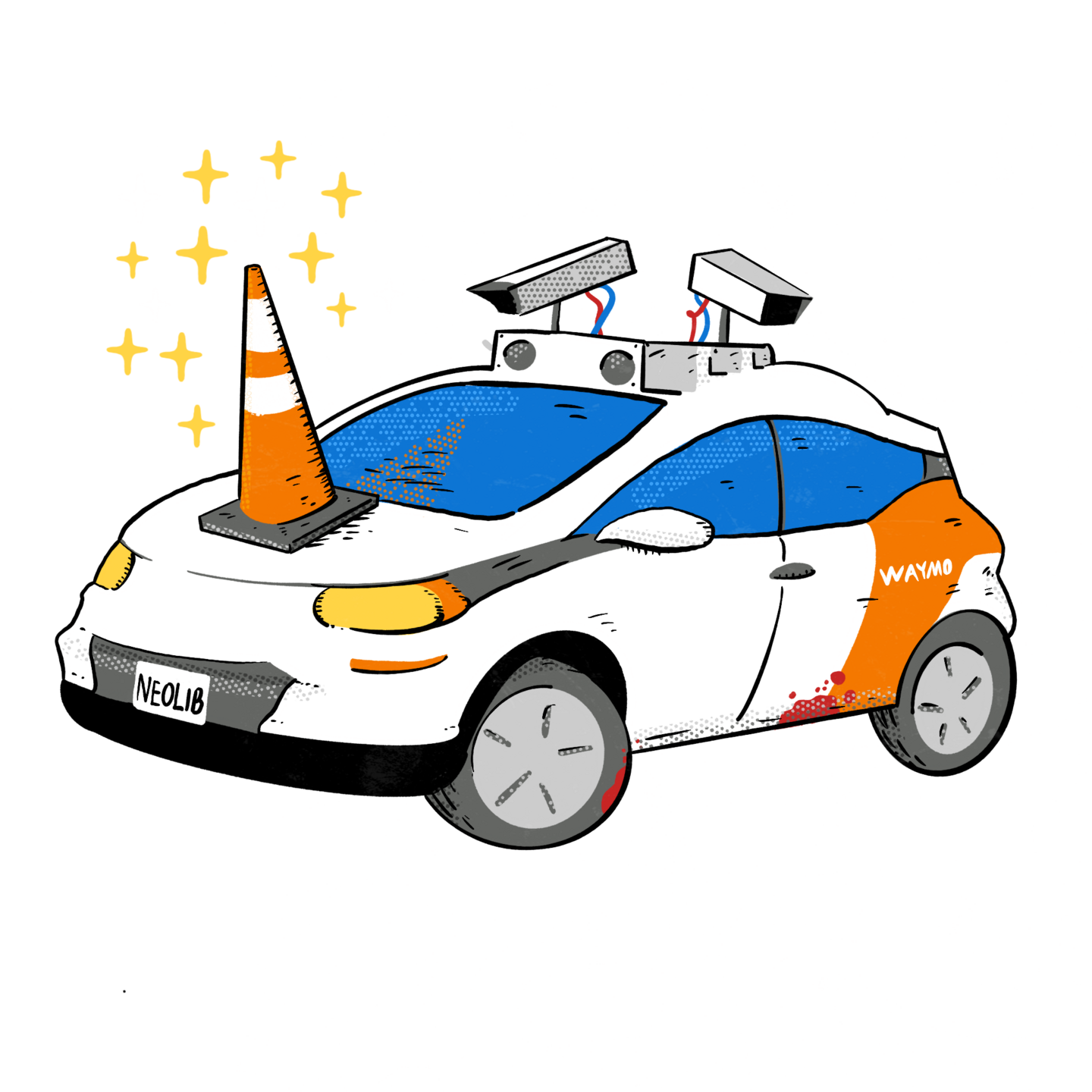

But over the past year or so, there’s been a push to bring back some of that hype and have it surround Google’s Waymo and General Motors’ Cruise divisions. They’ve been broadening the scope of their supposed robotaxi services in San Francisco and slowly expanding them to a number of other cities around the United States. The suggestion was that their services had moved beyond the “move fast and break things” ethos exemplified by Uber and Tesla. Instead, they claimed to take their time, play it safe, and that the strategy was reaping dividends. Autonomous vehicles had arrived, or at least were on the cusp of it.

That narrative, backed by little evidence, not only got more cities to approve robotaxi services, but even convinced the California Public Utilities Commission to approve a deeply contested expansion in San Francisco as recently as August that even local officials spoke out against. Yet, in the past month it’s completely unraveled as the PR deceptions have been unable to hold back the flood of truth that the services are not ready and shouldn’t be operating on public roads.

Cruise’s robotaxi disaster

For as long as Waymo and Cruise vehicles have been plying the streets of San Francisco, there have been stories about their frequent problems. The vehicles have been found to block emergency vehicles and transit, cause long traffic jams, pool in random parts of the city, create new threats for pedestrians and cyclists, and have even killed a dog. The companies always argued those were exceptional circumstances and the reality was that they were constantly getting better and deserved permission to keep going.

On October 2, that all changed when a pedestrian was hit by a passing vehicle that pushed her into the path of a Cruise driverless taxi. The Cruise vehicle proceeded to run over her before stopping briefly, then dragging her 20 feet (6 meters) as it pulled to the curb, while seemingly not being able to detect that the woman was underneath. That caused her serious injuries, and on October 25 Mission Local reported she was still in hospital in serious condition.

But that’s not the end of the story. On October 17, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration launched an investigation of Cruise’s entire fleet over the threats they pose to other road users, and on October 24, the California Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) suspended the company’s license to test driverless vehicles and charge passengers for ride in them. A couple days later, Cruise paused its autonomous testing across the United States in an effort to save face and followed up with a recall of 950 robotaxis on November 8.

The problem for the California DMV isn’t just what the Cruise vehicle did. It claims the company also withheld information. Specifically, the agency says the video Cruise provided to it after the collision only showed the vehicle hitting the woman, not her subsequently being dragged along the road, and that its officials only found out that happened from conversations with another government agency. That’s why it took a few weeks after the event for Cruise’s license to be revoked.

Since that last incident, more details have slowly emerged to paint an even more damning picture of Cruise’s operations. The New York Times spoke to company insiders who blamed Cruise chief executive Kyle Vogt for placing speed over safety in a bid to beat Waymo. He reportedly “wanted to dominate in the same way Uber dominated its smaller ride-hailing competitor, Lyft.” Matthew Wansley, a professor at the Cardozo School of Law in New York, said Vogt was “very Silicon Valley” — and that’s not a compliment.

Cruise had hundreds of vehicles in San Francisco, and despite the appearance of autonomous driving, they were supported by a massive operations staff equivalent to 1.5 workers per vehicle who intervened remotely every 2.5 to 5 miles (4 to 8 kilometers) because the supposedly autonomous driving system encountered so many situations it couldn’t properly navigate. It’s no surprise then that the company knew its vehicles had some major safety issues and kept them on the road anyway.

According to internal materials reviewed by The Intercept, Cruise knew its vehicles “struggled to detect large holes in the road and have so much trouble recognizing children in certain scenarios that they risked hitting them.” Internal testing found a considerable risk of colliding with children and that the system could lose track of them when they were at the side of the road. Despite that, Cruise was planning a major expansion to as many as 11 new cities.

A history of self-driving failure

Whether Tesla, Uber, Cruise, or Waymo, the assertion we’re supposed to believe is that if we let a computer start driving our cars, there’s no way they won’t be safer because us humans are flawed in so many ways that the machines are not. The companies don’t need to provide any evidence that their robotaxis or driverless cars or whatever they want to call them are actually safer than humans. They simply state it as fact and expect us to believe it — and far too many have fallen for it.

Yet, in the decade since all this hype kicked off, the proof is still lacking. We have plenty of examples of them performing very poorly and after all this time — long after we were promised ubiquitous self-driving cars by the likes of Elon Musk, Travis Kalanick, and Sergey Brin — they still have serious flaws that have not been addressed. Despite its public-facing rhetoric, The Intercept found that Cruise’s internal goal was to be as safe around children as an average Uber driver — and it wasn’t clear it could even do that.

Everything about this Cruise scandal reminds me of what happened with Uber in 2018: the “move fast and break things” approach that put corporate success before public safety, the corporate deception over the capability of their technology, the pressure being placed on rank-and-file workers by the chief executive, the shut down of the service once the scale of the problem was revealed, and even the further leaks that revealed even bigger issues the company was trying to hide.

We’re still early in this Cruise scandal and there’s surely more to come, but Uber’s self-driving program never recovered. It was offloaded onto Aurora in 2020 in exchange for Uber investing $400 million in the company, and I wouldn’t be surprised if this is the death knell for Cruise’s ambitions too. General Motors bought Cruise in 2016 for $1.1 billion, seeing not just the hype around autonomous driving, but also how Tesla’s valuation was far higher than could be reasonably justified because it convinced investors its self-driving tech would yield much greater returns than its electric cars in the near future. In short, it was valued as a tech stock instead of a traditional company, and General Motors wasn’t the only one trying to get a similar boost.

However, just like the other self-driving companies, Cruise hasn’t been able to deliver and the cheap money that fueled those big bets has largely dried up as interest rates have jumped over the past year. From January to September 2023, General Motors recorded a $1.9 billion loss on Cruise — and now it’s not even pulling in the meager fare revenue. Vogt has already said layoffs are coming for Cruise, and it’s hard not to feel this is the final nail in the coffin of GM’s robotaxi experiment as it also has to fund an expensive shift to electric vehicles.

Don’t buy the fantasies

In the aftermath of this incident, there’s going to be a push to frame this as a Cruise issue rather than one with the broader push to make robotaxis a reality and convince us they’re a better and safer alternative. There’s already been a narrative that Cruise is the bad actor while Waymo is doing virtually everything right. But that needs to be resisted because it’s simply not true.

Waymo vehicles have also been recorded blocking public transit and other drivers. They’ve crowded quiet neighborhoods for no discernible reason and have gotten in the way of emergency vehicles on numerous occasions. One drove into a hole in a construction site at the beginning of the year, and remember the incident where a robotaxi killed a dog? That was also Waymo’s fault.

Even though state authorities initially gave Waymo and Cruise the green light to expand in San Francisco, the city has been pushing back and using the levers it controls to force them to abide by local rules wherever possible. More cities should do the same, but there’s a bigger picture to consider here. The tech industry positions autonomous cars and robotaxis as the solution to many of the transport problems we face — from road deaths to inequitable access — but the past decade has shown us that was a clear deception.

Addressing the problems on our roads won’t come from flawed technologies pushed by powerful corporations, but getting to the root causes: things like poor road design, an overreliance on cars, and the size and weight of the vehicles on our roads. Other countries and cities around the world have already made their roads much safer than those in the US and it’s not because they found a way to make driverless cars or other tech solutions work where the US couldn’t.

The longer we’re distracted by tech fantasies, the worse it will be for everyone who uses public roads. The Cruise incident and the ongoing failure of Tesla’s autonomous system to deliver real improvements are the perfect opportunity to stop waiting for the tech industry to save us, and do the far less sexy but much more important work of redesigning roads, investing in transit, and following the evidence instead of listening to well-paid tech PR teams. We can build a better future than one where our roads are clogged with robotaxis.