Robotaxis Won’t Get Us There, So Let’s Stop Being Used to Sell a Future that Doesn’t Serve Us

Editors note: The original article by Anna Zivarts & Cecelia Black is on DisabilityVisibilityProject.com . We highly recommend visiting and subscribing to the Disability Visibility Project in order to learn much more about disability issues.

Transportation is one of the biggest barriers for people with disabilities. According to the National Household Travel Survey 7 out of 10 Americans with travel-limiting disabilities reduce their daily trips because of transportation barriers. Lack of transportation is one of the factors contributing to much lower employment rates for disabled people. The Center for American Progress reports that in 2021, nondisabled workers were three times more likely than disabled workers to be employed.

So it’s no surprise that robotaxi companies are latching on to the potential benefits to nondrivers as a reason for the rapid deployment of autonomous vehicles (AVs). But let’s step back and consider what we have to gain, and what the costs of an unquestioning embrace of autonomous vehicles would mean for disabled community members. In this conversation, it’s really important to consider who within the disability community benefits, and who might be harmed.

The first, big glaring question is access. This past September, Cecelia attended the launch for Cruise’s accessible autonomous vehicle program where she listened to disabled leaders and Cruise and GM executives talk about the importance of partnerships with the disabled community and the potential of autonomous vehicles. Afterward, they toured a prototype of one of Cruise’s Origin vehicles, designed for wheelchair accessibility. It struck her that as Cruise was actively testing their standard AV fleet on the streets of San Francisco, they still hadn’t answered basic questions, like how to secure a wheelchair, for their accessible AV program. Neither Cruise nor Waymo has deployed a wheelchair accessible vehicle, and there is no timeline for deployment.

Currently AVs are largely unregulated and are not required to meet any accessibility standards at the federal or state level. Despite AV pilot programs operating in several states none are fully accessible.

To truly expand transportation access, AVs need to accommodate people in the disability community who are not already served by standard vehicles. That means all stages of an AV trip, from scheduling and boarding a vehicle to navigating en route and disembarking, must be accessible to people with cognitive, developmental, visual, auditory and mobility disabilities. This poses real challenges for driverless vehicles. For example, a wheelchair user with very little upper body mobility needs to be able to navigate an app, a loading zone and a vehicle ramp and secure themselves without the help of a driver. Someone who is blind needs to be able to both find the correct vehicle, and when the vehicle drops them off, needs to be oriented so they can continue safely to their destination. And if delays or detours occur, there must be communication about what is happening and why.

Next is the question of cost. We’ve seen what happened with Uber and Lyft and other ride hail companies. (Uber’s average US fare-per-trip rose 83% between the third quarter of 2019 and the third quarter of 2022). First they were massively subsidized and so for many of us in the disability community, in particular Blind and low vision people like Anna, our mobility options expanded. But now the costs have gone up (and it’s not that drivers are earning more), meaning that except for the wealthiest in our community, ride hail has become only something affordable as a rare luxury or in emergency situations. What is to say that robotaxis, who will be operated by private companies, will end up being any more affordable?

“In the Blind community, not all Blind people have good jobs. Students and others are struggling financially, and Uber is expensive,” shares Amandeep Kaur, a Blind nondriver who Anna interviewed as part of the Transportation Access for Everyone storymap project at Disability Rights Washington.

According to the Center for American Progress, disabled adults are twice as likely to experience poverty than their nondisabled peers. And nonwhite disabled people are more likely to struggle with transportation costs. The Century Foundation reported that in 2020 one in four disabled Black adults lived in poverty compared to just over one in seven of their White counterparts.

There’s also the question of geography. Ride hail does not exist in more rural and lower income areas. During the pandemic, it was almost impossible to get even in some of the largest cities in Washington State. Will robotaxies be any different as the fleet owners and operators, like the venture-funded companies, choose to prioritize profits over access for underserved areas?

And we can’t forget about the safety for people outside of vehicles. The Disability Rights and Education Defence Fund (DREDF) released a report last November raising serious concerns about the lack of representation of disabled people in datasets used to train and test autonomous vehicles. At a congressional hearing in March, DREDF testified: “A lack of disability representation within datasets creates significant risk for disabled people. AV developers define what constitutes “normal” human appearance and movement for the purposes of identification by an AV’s decision-making…For example, a researcher tested a model with visual captures of a friend who propels herself backward in her wheelchair using her feet and legs. The AV’s system not only failed to recognize her as a person but indicated that the vehicle should proceed through the intersection, colliding with her.”

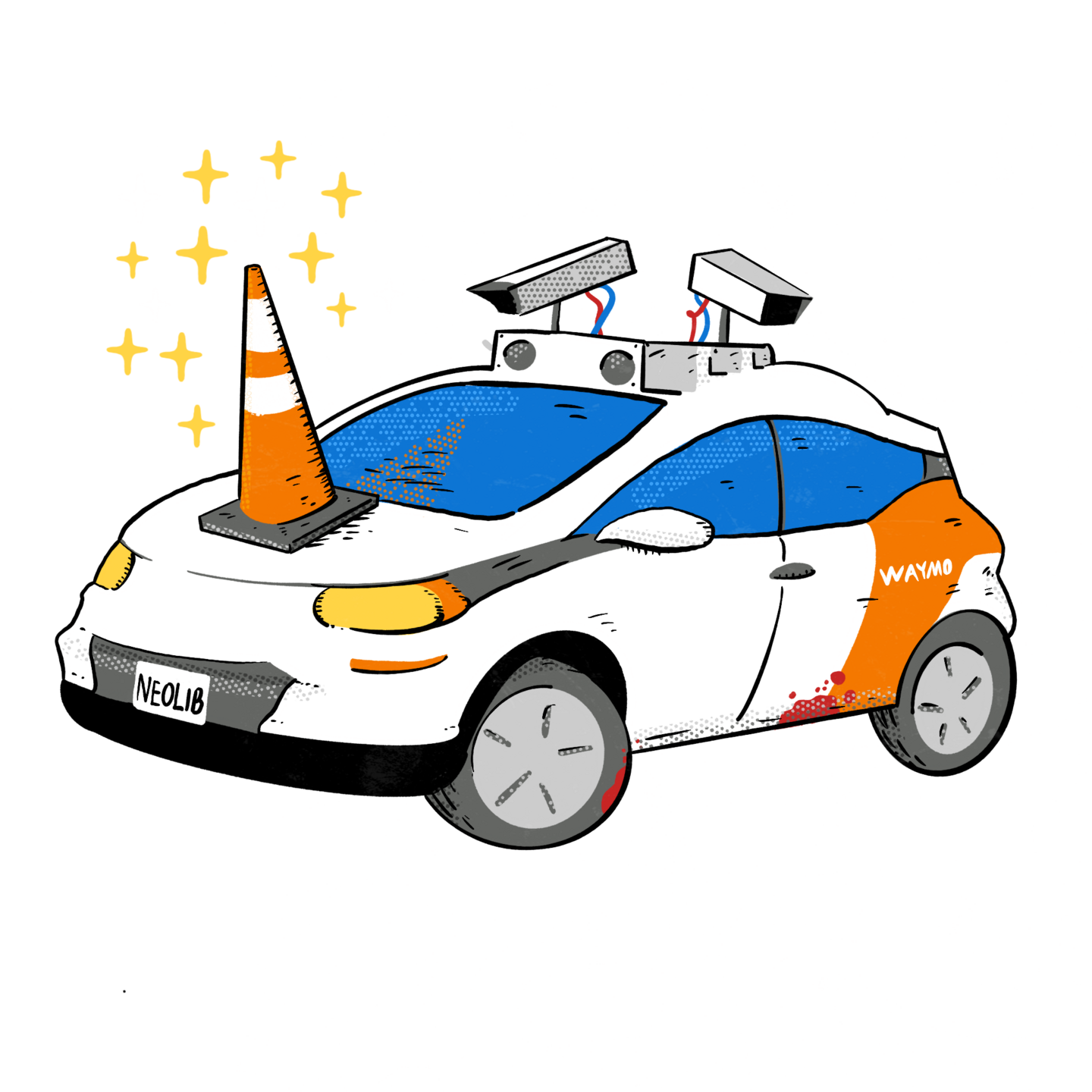

AVs have additional problems navigating unpredictable traffic situations like construction zones, emergency scenes, and missing street markings, not to mention AVs ongoing challenges with making left turns. Cruise recently suspended operations after one of their robotaxis in San Francisco decided to try to pull over after hitting a pedestrian, dragging her under the vehicle for 20 feet at 7 miles per hour.

These unpredictable situations created for example by missing street markings like crosswalks, become quite common when considering the massive gaps in pedestrian infrastructure throughout the country. It is also these exact situations that put people with disabilities at greater risk even before the introduction of autonomous vehicles. Pedestrians in wheelchairs are 36% more likely to die in traffic accidents. Missing sidewalks and construction zones regularly force wheelchair users to use the street alongside cars. In 2021, Toyota specifically acknowledged the difficulty of operating self-driving vehicles in situations with visually impaired pedestrians after one of its autonomous “e-Palette” shuttles hit a visually impaired paraympian during Tokyo’s Olympic games. AVs’ poor track record together in these situations only compounds the safety concerns for pedestrians with disabilities and older people.

But even if we get accessible robotaxis that can safely move around cities, around children, in all kinds of weather, that are miraculously affordable and serve lower-income and less dense communities, it’s critical to ask if this is actually the future we want. We need to proactively consider the larger land use and public health impacts if autonomous vehicles succeed. Just as wider roads and highways induce more driving, longer commutes and unsustainable, sprawling suburbs, making driving less stressful or attention demanding from drivers will likely induce longer commutes and trips (for example, if you can do a work call, watch a movie, or read a book to your kid while you drive, you may be willing to live forty miles away from where you work or the nearest grocery store). Such land use patterns that essentially require driving to access basic services will be seriously detrimental to those of us who can’t use or can’t afford autonomous vehicles. If we are serious about stopping climate change and creating more rollable, walkable communities with essential services within easy reach of every household, the acceptance and promotion of autonomous vehicles punishes us in exactly the opposite direction.

We are accustomed to placing our hopes and dreams in new technologies that remove barriers and increase inclusion. We want this access. We dream of a day when our disabilities won’t prevent us from fully participating in our communities. And so when AV companies invest resources in outreach to the disability community, promising us a more inclusive future in exchange for our stories and our support, we want to believe they can deliver. But we need to remember these companies are ultimately answering to the interests of investors. If our needs are inconvenient or costly, we see how quickly they can be ignored.

After their recent pedestrian-dragging incident, Cruise suspended driverless operations, and halted production of their Origin vehicle, which was the vehicle that was supposed to provide wheelchair accessible mobility. Once again, the date that autonomous vehicles will deliver easy and accessible mobility got pushed further into the never-quite-arriving future.

But we don’t have to wait for a technology solution that may not ever arrive. Real solutions, real access, will come from rethinking how we build communities to be more inclusive through more affordable, accessible housing, and land-use decisions that prioritize access to needed services and frequent and reliable transit. Instead of allowing ourselves to be distracted by promises of future technology that will only exist if it generates profits, we must remember that we can create the change we need right now. It’s a matter of organizing, of building power and demanding that we can build and must build communities that are accessible to everyone.

See original article on DisabilityVisibilityProject.com

Cecelia Black is a quadriplegic and wheelchair user. She is a transit organizer for Disability Mobility Initiative at Disability Rights Washington. Black is a photographer and founder of Access Test Collective, a multimedia art project focused on sidewalk accessibility. Black has a masters in public policy and is board president of Be:Seattle, a tenants’ rights organization in Seattle.

Anna Zivarts is a low-vision mom and nondriver who was born with the neurological condition nystagmus. She directs the Disability Mobility Initiative at DIsability Rights Washington and launched the #WeekWithoutDriving challenge. Zivarts serves on the Pacific Northwest Transportation Consortium advisory board and the National Safety Council Mobility Safety Advisory Group. She is publishing a book with Island Press about the expertise of nondrivers.