New York Magazine – The Self-Driving Car Bubble Has Popped

Editors summary: Apple canceled their EV/AV program, simply because they could not make it workable. Despite the hype, self-driving is far more complicated than most people thought. A bit of successful self-driving doesn’t mean that the fantasy can or should always work.

See also Barrons article The EV Stock Bubble Has Popped. This One [robotaxis] Is Over, Too from 12/13/2023

Original article by John Herrman from New York Magazine

Apple has spent nearly a decade not-so-quietly trying to build a car. It poached big shots from Tesla, Ford, GM, BMW, Mercedes-Benz, and Lamborghini as well as Alphabet’s car company, Waymo. The project, known internally as Titan, cost billions of dollars and accounted for thousands of jobs, but last week, Apple abruptly called it quits.

At Bloomberg, Mark Gurman reports on a few likely causes: The project was plagued by vague plans and false starts, and some key executives were skeptical from the start. The project was spurred by Tesla’s success, but, Apple being Apple, the company wanted to release something fully formed and different from existing products — a visually distinct electric vehicle that could drive itself. Crucially, as the car’s release target drifted toward 2030, the entire project was starting to fall out of step with industry and economic trends. EV sales are plateauing for the time being, the high end of the market is saturated, and the price target for Apple’s car was reportedly somewhere around $100,000.

The Apple car’s biggest problem, though, was that the company simply couldn’t make it work. Near the beginning of the project, which was established in 2014, Apple decided its car needed to be able to drive itself. At the time, this seemed like a hard problem that multiple companies might have been on the cusp of solving. In 2015, Tesla was already shipping cars with a feature called Autopilot. Google had been on the case since the late 2000s and said it was making brisk progress. There were dozens of well-funded self-driving start-ups, many of which were acquired by car manufacturers. Uber was confidently staking the future of its business on getting rid of human drivers. By 2017, much of the car industry was breezily predicting the arrival of substantially self-driving cars by the early 2020s at the latest.

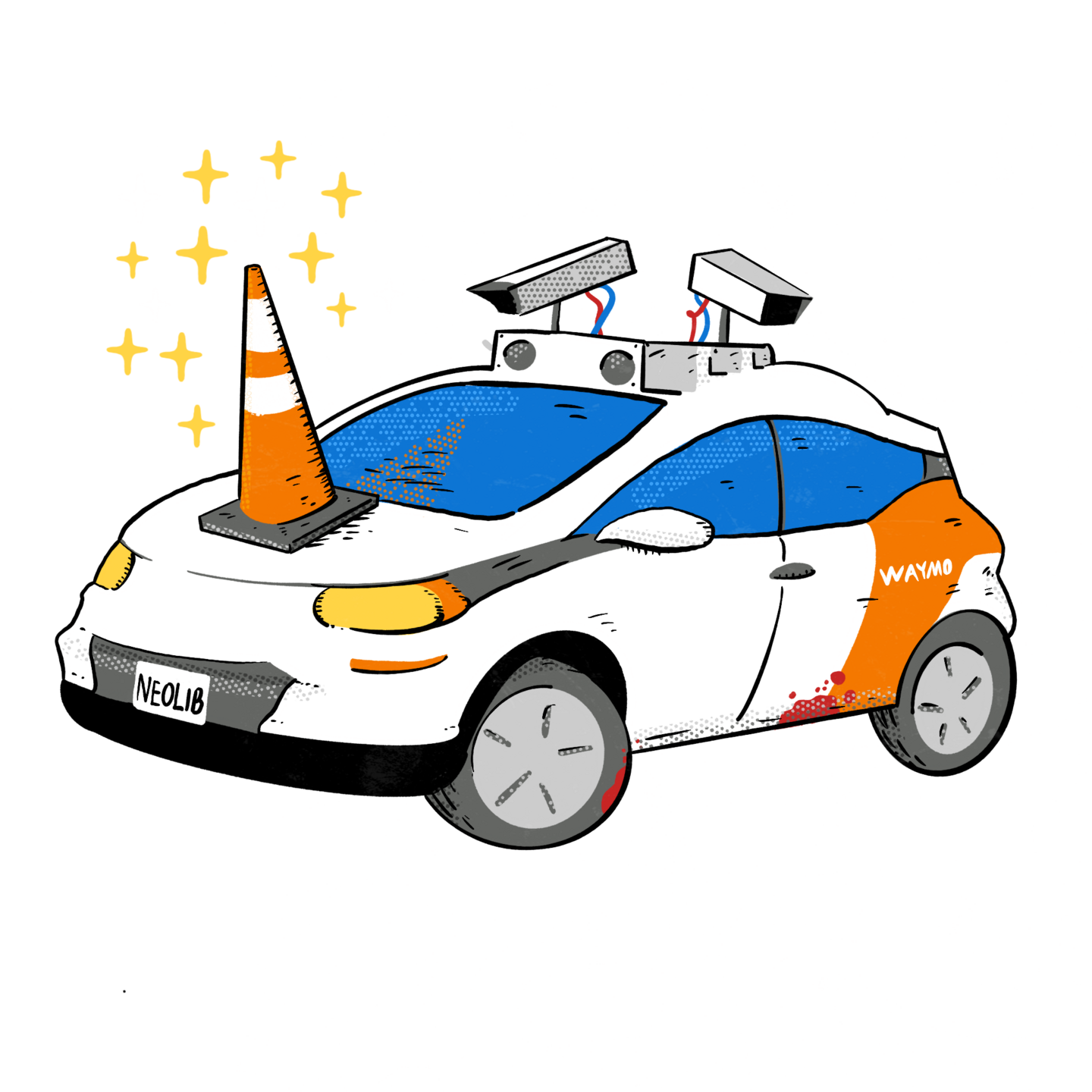

That’s not what happened. Tesla has blown through countless promises by Elon Musk that fully autonomous cars were just one more year away and is facing fresh scrutiny after an engineer died while using his Model 3’s “full self-driving” feature; in October, Musk admitted that he’d been “overly optimistic” about the technology. Uber stopped developing its own AVs. Ford and Volkswagen abandoned a joint project, Argo, after billions of dollars of investment. GM-backed Cruise has recalled its taxis from San Francisco streets after one of them struck and dragged a woman down the street. (The company is losing GM $2 billion a year, and just last week its valuation sliced in half.)

Every firm in the race to build a self-driving car was running into the same few real-world obstacles (and, occasionally, other cars), namely unpredictable drivers and wildly diverse environments and road conditions. The range of possible scenarios that a self-driving car might face on a single trip to the store is astronomically huge, and the risks of failure include death. For other automakers, revising plans around autonomous cars was expensive and embarrassing. For Apple, it ultimately meant retiring the entire project. The closest thing the public saw to an Apple car was a Lexus SUV with a big Apple-y sensor array on top:

If anything, Apple’s move is a pretty late signal that the self-driving bubble has burst, but it’s a clear one. Apple isn’t a start-up or an automaker trying to catch up with Elon Musk’s tweets. At the end of 2023, it had more than $70 billion in cash on hand. It wasn’t running out of money to invest in a problem it had nearly solved. It’s a highly motivated firm with existing connections to the automotive industry and nearly infinite resources realizing that its plan might not be feasible for the foreseeable future.

Even with the benefit of hindsight, the hype around imminent self-driving cars was understandable. Tesla’s early self-driving features were impressive and had been developed quickly — their insufficiency for actual sustained driving was easy for the company to characterize as the product being merely unfinished, and its failures as a tidy to-do list for the next version. Likewise, self-driving taxis have been on the streets in a few cities for years now. Their presence implies a technology that’s nearly complete — an artificial-intelligence system that just has a few more things to learn — but in actuality demonstrates something more like a developmental plateau, not to mention the unexpected social and regulatory challenges.

In other words, this is a story about the AI and the stories it helps tell about itself. As the automotive journalist E.W. Niedermeyer has written, “Like Large Language Models, driving automation is a technology that draws us into a fantasy, thinking a vehicle ‘can drive itself’ after a few minutes of plausible performance.” Early self-driving tech created a larger fantasy of inevitability so strong that it swept up one of the largest companies on the planet. Meanwhile, its peers were realizing that the future of software-assisted driving looked less like “autonomous cars” — a goal with conceptual and practical parallels to “artificial general intelligence,” the holy grail for firms like OpenAI — and more like what we have today: modest but genuinely useful driving-assistance tools and safety features — adaptive cruise control, lane assist, emergency braking — in most new cars.