NY Times – How Safe Are Driverless Cars in China? I Rode in Some to See.

Editors note: China has an effective solution for promoting autonomous vehicles. They simply censor reports of crashes and safety incidents in both the news media and social media. Hey, if you don’t hear about the deadly crashes then they must be safe!

See original article by Keith Bradsher at NY Times

Computer-aided driving has official support and public acceptance, but state media seldom reports crashes or safety incidents, and online posts are censored.

Images of the burned vehicle flew through the Chinese internet: An Aito M7 Plus electric sport utility vehicle, operated by an advanced assisted driving system, had crashed on a highway in Shanxi Province on April 26.

A woman who said her husband, brother and son had been killed posted videos online and pleaded for an investigation. All of her postings soon vanished, and she said she would not discuss it further.

A Chinese business news outlet published a lengthy online investigation that questioned the safety of assisted driving systems. But that soon disappeared, too.

State-run national media refrained from covering the crash for nine days after it happened. Then they posted a statement from Aito Car, a Chinese brand, that disavowed responsibility. The statement said that the car’s automated braking system had been designed for speeds up to 53 miles an hour, but the car was going 71 when it hit the back of a road maintenance vehicle.

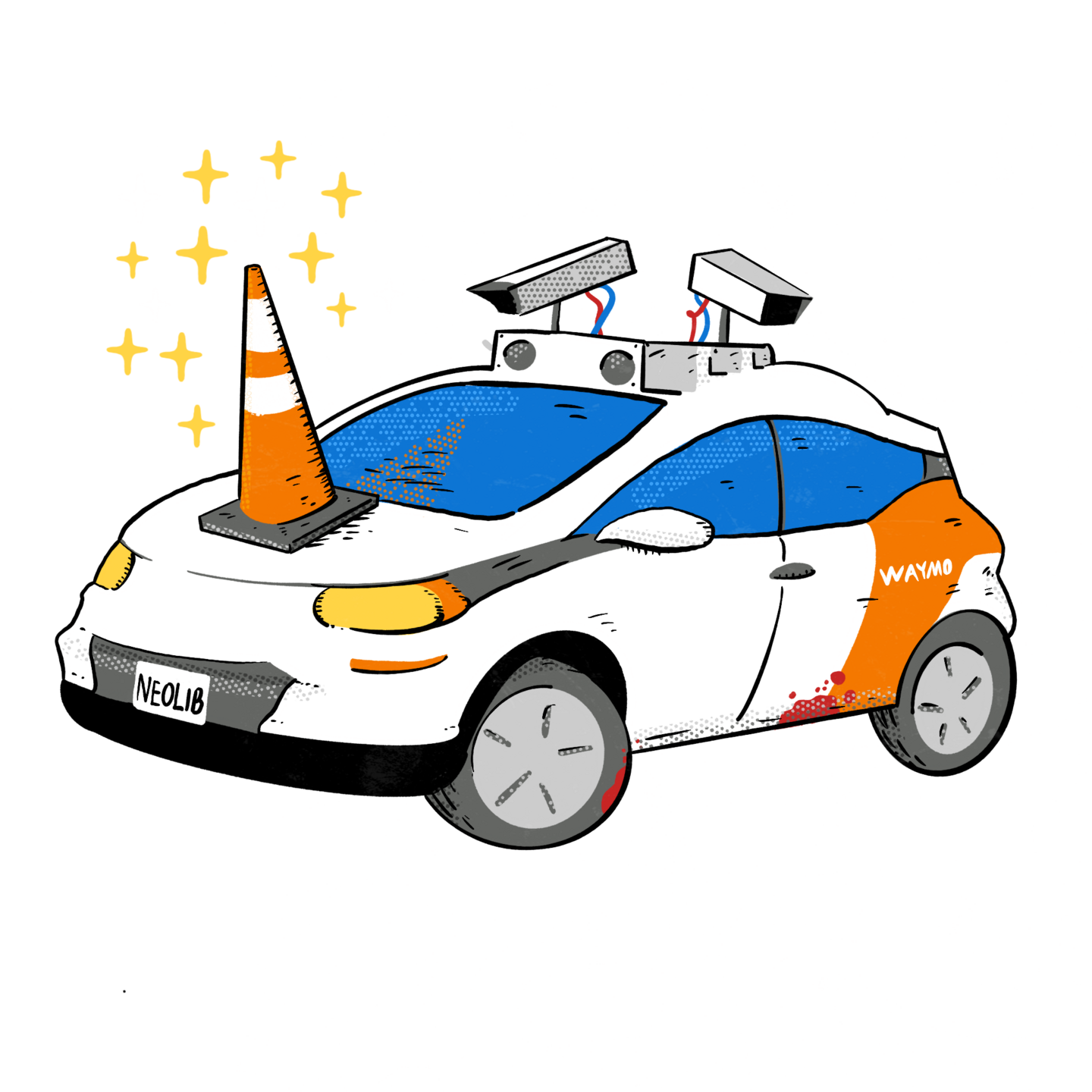

In the United States, a similar crash would probably have attracted considerable attention and possibly government or legal scrutiny. The main companies using computer-guided driving technology in the United States — Tesla, Waymo and Cruise — have all been subjects of high-profile safety investigations.

Waymo, which was started as Google’s self-driving division, has been testing driverless cars in Phoenix but faces a review by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. General Motors has resumed testing its Cruise robot taxis in Phoenix, after one of them in San Francisco dragged a pedestrian who had been knocked into its path by a human-driven car.

Far less public and official scrutiny exists in China, where the government strongly backs the technology and tightly limits public information about accidents. The Ministry of Transport issued safety rules in December that are designed to foster a broad shift from people to computers in car driving.

“The development environment of my country’s autonomous driving industry is becoming increasingly perfect, providing possibilities for the implementation of autonomous driving vehicles,” Wang Xianjin, the ministry’s deputy research director, told the official Xinhua news agency.

The government has not issued statistics on safety incidents involving driverless cars or advanced assisted-driving technologies, like automated lane changes and obstacle avoidance on highways. Chinese car industry executives say these technologies are safe.

The tech giant Baidu, which works with automakers, is testing its own fleet of driverless taxis in the city of Wuhan.

“Small scratches and dents are inevitable, but we have never had any major casualties,” Wang Yunpeng, president of Baidu’s intelligent driving business group, said in a speech.

Over two days last month, I went for six rides in Baidu robot taxis in Wuhan. On one of the trips, with no safety driver ready to take over, the vehicle slowed nearly to a stop in fast-moving traffic on the upper deck of an expressway bridge high above the Yangtze River.

The car was trying to move from the center lane to the right lane, in preparation for an exit. The driver of a blue car in the right lane that was slightly behind my car began slowing to let my car in front of it. But my car also kept slowing. It started beeping its horn automatically to yield the right of way, instead of accelerating to enter the adjacent lane. Both cars kept slowing until they were barely moving.

A third car, moving at highway speed, whipped around both cars. The robot taxi finally inched slowly into the right lane ahead of the blue car and then accelerated before taking the next exit from the bridge as planned.

I asked Baidu if it could look into what might have gone wrong. A spokeswoman said that the incident was an unusual circumstance and that drivers in Wuhan were seldom so willing to yield the right of way. She said the company would study the incident and consider whether to adjust the algorithms that control its driverless cars.

Many drivers in Wuhan are indeed fairly aggressive. I saw a different robot taxi stop at a pedestrian crossing to allow people to walk across the street, only for motorists to blow their horns impatiently.

A year ago in Suzhou, I took a 10-minute journey in a robot taxi operated by a Chinese start-up. The taxi incorrectly made three emergency stops. But though my colleagues and I were thrown forward against our seatbelts, there were no collisions or injuries.

A safety driver who was in the car with us explained that cautiously programmed software had wrongly identified pedestrians or parked cars as being about to enter the car’s path.

Numerous government ministries and other agencies have claimed a role in the development of self-driving cars. But none have direct responsibility for regulating their safety.

Chinese companies have done extensive experiments to gather data on how autonomous cars interact with pedestrians, who are far more numerous in Chinese cities than in most American cities. At a former steel mill on the northwest outskirts of Beijing that is now a public park, Baidu is running a three-year experiment in which robot taxis slowly and carefully maneuver through crowds of people.

An interagency task force led by the Ministry of Transport set a few broad rules for safety last December. Most robot taxis are no longer required to have safety drivers, but one remote operator must be assigned for every three vehicles. The task force has deferred more detailed rule making until the start of 2026.

Companies are trying to make as much progress as possible before that deadline, so they can influence the shape of the final rules. Whoever develops the most used system could reap a bonanza.

The cost of assisted driving and driverless systems lies mostly in developing them, not in manufacturing them. Whoever sells the most can spread development costs widely.

Yet safety concerns persist in China. A news outlet in Hainan Province posted an article at the top of its website on June 7. The article described how a Xiaomi SU7 electric sedan with an advanced assisted-driving system seemed to have accelerated out of control, killing one person and injuring three. Within three hours the article was fourth in a national ranking of most-viewed news items.

Xiaomi soon issued a statement saying there was nothing wrong with the car that crashed. The article suggesting otherwise then disappeared from China’s internet, except for a few screenshots taken by internet users.

Li You contributed research.

See original article by Keith Bradsher at NY Times