Bloomberg – Robotaxis Are No Friend of Public Transportation

See original article by David Zipper at Bloomberg

AV companies like Waymo are promoting the idea that driverless technology can complement transit service. Recent ride-hailing history suggests otherwise.

Last week, Waymo, the Alphabet Inc.-owned robotaxi company that offers self-driving rides in parts of San Francisco, Phoenix and Los Angeles, announced a new initiative that it described as “an important step toward making clean transportation more accessible.”

From now until Nov. 15, customers who use Waymo to connect with one of eight transit stops in the San Francisco Bay Area will receive a $3 credit toward a future Waymo trip. According to the company, the promotion is part of its support for “more walkable, bikeable, and transit-rich communities.”

The new offer is part of an ongoing campaign to sell autonomous ride-hailing as an asset to cities and transit agencies. To help make its case, Waymo recently hired a transportation policy director from the Bay Area urbanist think tank SPUR, and the Chamber of Progress, a trade group that represents big tech companies, has lobbied California regulators to greenlight the autonomous vehicles offered by Waymo and its rival Cruise. The companies’ battery-powered AVs, the organization argued, “provide access to transit for the elderly, disabled, and those living in underserved communities.” (An exception to this charm offensive is Elon Musk, the robotaxi-hawking CEO of Tesla Inc., who has long disparaged public transit.)

Transit-robotaxi synergy is an enticing message at a time when public transportation agencies face a dire funding shortage , and it could especially resonate among left-leaning residents in places like the Bay Area who value buses and trains even if they seldom use them.

But caveat emptor: The robotaxi industry’s embrace of public transportation conceals a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

To understand why, let’s begin by looking more closely at Waymo’s new Bay Area promotion, which attracted significant local news coverage . For one thing, how will the company know that someone who takes a robotaxi to a station actually uses transit upon arrival instead of heading to a nearby restaurant and pocketing the credit? Unless Waymo is syncing with transit trip data — a step that is technically difficult and potentially problematic on privacy grounds — that is infeasible.

In an email, Adam Lenz, Waymo’s head of sustainability and environment, told me that the company can’t currently link robotaxi trips to transit rides, but said “we hope that such integrations are possible in the future.”

Here’s another question: Where, exactly, will pickups and drop-offs occur, since at least some of the transit stations included in Waymo’s promotion (like West Portal, a Muni Metro station) do not have dedicated curbside space for ride-hailing and robotaxis? If Waymo’s promotion leads to a spike in connecting passengers, double-parked vehicles could snarl traffic and endanger passengers scrambling to and from the curb. Lenz said that Waymo had given advanced notice of the promotion to BART, Muni and Caltrain, but a BART spokesperson told the San Francisco Standard that the agency was unaware of Waymo’s initiative until it was announced (suggesting that staff had no opportunity to adjust station layouts to accommodate an uptick in robotaxis).

The good news, if you can call it that, is that these concerns are largely theoretical, because any resulting disruption to Bay Area transit operations will probably be minor. The reason: Even with a $3 credit, few travelers are likely to take journeys that combine transit and robotaxis.

To understand why, consider what researchers learned about the ride-hailing industry over the last 15 years. (The user experience of getting a Waymo is basically the same as requesting an Uber, just without the human driver.) When smartphone-powered, on-demand car services appeared in US cities, academics, government officials and company leaders extolled the potential of app-based rides to resolve transit’s supposed “first mile/last mile problem” of moving people to and from transit stations that are too distant for walking.

In 2016, the Federal Transit Administration funded five projects designed to see how many people would regularly use ride-hailing cars to get to and from stations. The answer: Not many. For example, in 2016 the public transportation agency serving St. Petersburg, Florida, offered riders $5 off an Uber ride that originated or ended at a transit stop (a promotion that resembles Waymo’s new Bay Area promotion). On an average day, a subsequent analysis found, just 40 people participated in the program, representing less than 1/1000th of the system’s riders.

Had the study been held in San Francisco, the results are unlikely to be markedly better: According to a 2022 study of the region, just 0.4% of the region’s transit journeys included a ride-hail trip.

The reasons why ride-hailing underperforms as a first- or last-mile solution are intuitive. People dislike transfers, and those paying for a car ride can generally afford to avoid them. When a passenger’s Uber or Lyft arrives, locating the vehicle outside a bustling transit station or bus stop can be stressful. Perhaps most importantly, regular transit riders — who generally have lower incomes than other travelers — can seldom afford to take an Uber or a Lyft as part of their regular commute.

Since robotaxis are comparable to ride-hailing in price as well as user experience, all of these transit-related limitations will probably apply to them, too. At the end of the day, summoning a car — whether driven by humans or computers — just isn’t a very practical way to get to or from a transit station.

In fact, a surge in self-driving cars would likely be a net negative for transit (even if the vehicles do not squat on transit lines and bus stations, as has happened repeatedly in San Francisco).

Read more: The Case For and Against Robotaxis

Again, consider what academics have learned from 15 years of experience with Uber and Lyft. A study earlier this year found that ride-hail trips in California were more likely to replace transit than any other mode. Previous research has concluded that the ascent of Uber and Lyft was a major contributor to falling passenger counts across transit systems nationwide prior to Covid.

Beyond luring away straphangers, ride-hailing worsens transit by increasing congestion, particularly due to “deadheading” miles driven without a passenger inside the vehicle. In San Francisco, local officials concluded that ride-hailing companies were responsible for most of the increase in congestion from 2010 to 2016. Unless buses have access to dedicated lanes — which are few and far between in most US cities — thickening traffic will slow down trips and nudge passengers to consider driving (or hailing a ride).

If robotaxis scale, there is every reason to expect them to poach transit riders and worsen bus service, just as ride-hailing has.

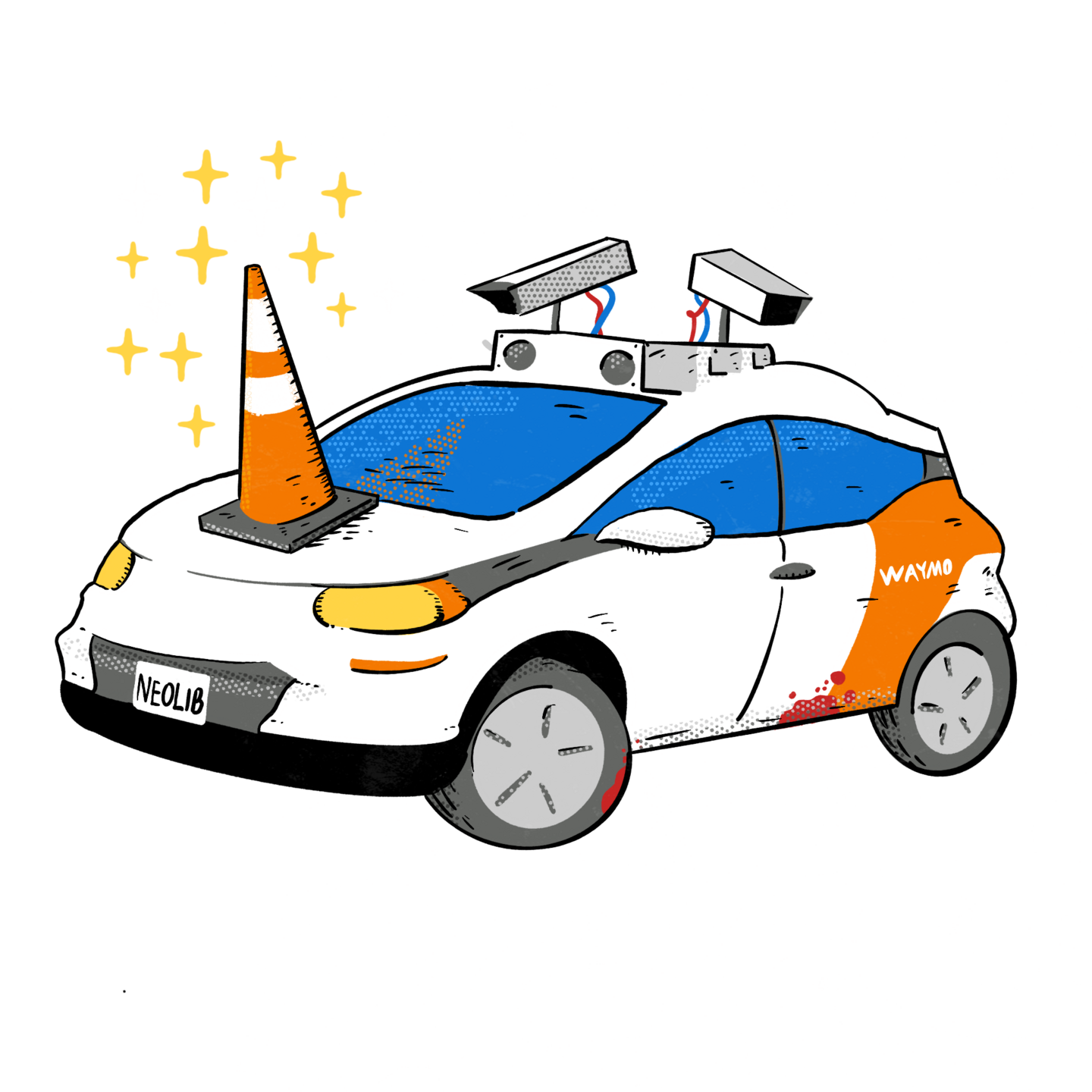

When one looks beyond the software and hardware that underpin their services, both robotaxis and ride-hailing rely on cars — the very vehicles that have undermined urban quality of life for a century. Automobiles inflict damage that many cities are now trying to reverse by encouraging transit or biking, which are far more space-efficient and sustainable than even an electric car, autonomous or not. That’s one reason why activists in San Francisco revolted against robotaxis last year by placing orange traffic cones atop their hoods , immobilizing them: They were sounding an alarm about self-driving cars further entrenching the Bay Area’s already autocentric transportation system.

Now we can see why the robotaxi industry could be eager to present itself as transit’s tech-savvy new friend. Many city residents rightly value buses and trains for their ability to liberate street space from cars and provide an affordable, convenient and clean way to navigate dense neighborhoods. Waymo may be hoping that if the company hugs public transportation closely enough, some of its urbanist glow might rub off on robotaxis.

It’s a smart political strategy. But make no mistake: It’s greenwashing.

See original article by David Zipper at Bloomberg