Wired – Get in, Loser—We’re Chasing a Waymo Into the Future

See full article at Wired

Wired did a really extensive article [archive] on them following around a Waymo for an entire day. Definitely worth reading. But interestingly, they actually make some great insights, which I have quoted here.

It is so much about novelty, not transportation:

WIRED happens to have a bureau in one of Waymo’s first markets, which is both an asset and a challenge: The novelty of being on the road with a bunch of robots has largely worn off for us in San Francisco, too.

Lack of demand during much of the day is rather an interesting subject that Waymo avoids:

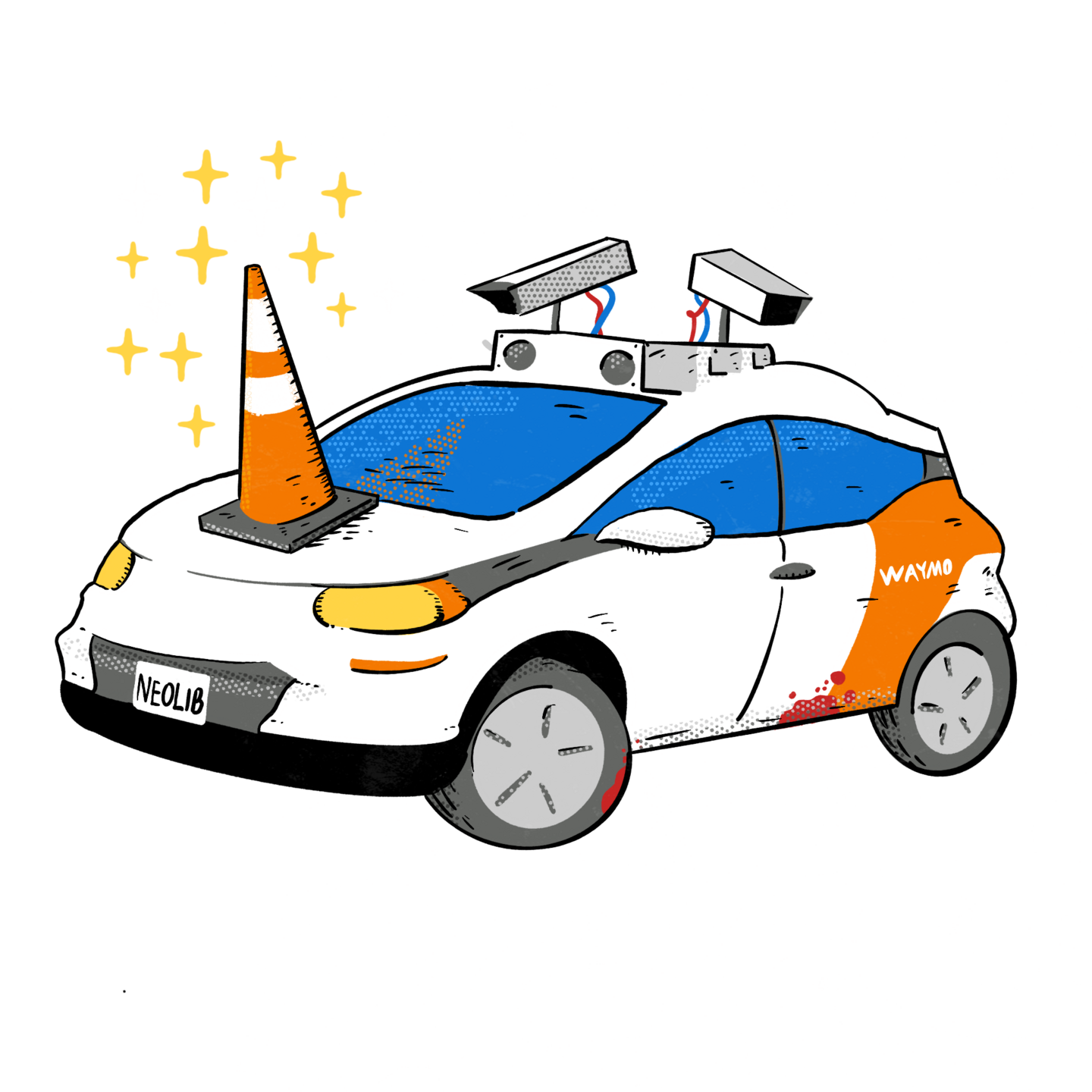

But the Waymo just sits there. For two agonizing minutes. Plenty of time for us to stare awkwardly at our quarry—a vehicle whose shape recalls a cartoon shark with a bunch of spinning doodads implanted in its skin—as it stares back at us through its 29 cameras and five lidars, mapping our contours.

Slow is not what riders are looking for:

Then, at 10:42 am, the Waymo starts to move. WIRED shouts, “Follow that car!”

Less than a minute later, Gabe sighs. “I’m not used to driving this slow.”

Yes, amusement park ride is the appropriate phrase. Many people, especially tourists, use Waymos only for the novelty. Once the novelty wears off…:

Riding around inside a self-driving vehicle, especially for the first time, is an immediately cool experience. It starts out like an amusement park ride—the empty gondola sidles up, you step in, you shut the door. Then it becomes the opposite of an amusement park ride. No thrills. No lurches. No clatter. Just you, some soft black leather, a default computer voice, and—for now—a steering wheel, ghostly turning this way and that.

Being slow means that once the novelty wears off people will not be interested in taking a Waymo:

From his sporadic prior experience sharing the road with Waymos, Gabe’s impression is that they’re pokey and plodding, rule-followers to a fault. So far our Waymo—license plate 53516F3—isn’t doing anything to break that stereotype. “It drives better than my mom, but she’s 85,” Gabe says. He gestures at the speedometer. “Look at it. Exactly the speed limit.”

Robotaxis are simply more cars, which is exactly what we do not want:

“Would you rather that there were more of these on the road than humans, just in terms of the driving style?” WIRED asks as our Waymo accelerates from a stop with the serenity of someone doing their morning tai chi. Gabe literally shudders. “I think that would slow down traffic tremendously.”

“But then there would be fewer lives lost,” WIRED says. “That’s the whole point.”

“I don’t know, would there really be that many fewer lives lost?” Gabe says. “People die in surface-street collisions very infrequently.” Then he ups the utopian ante: “I mean, we could do things to totally eliminate traffic deaths. What’s going to eliminate traffic and pedestrian deaths is moving cities away from being dependent on cars—and autonomous vehicles do exactly the opposite, by definition.”

“If this is the future of urban transportation,” he says, motioning up at 53516F3’s lidar-whirling rear end, “then we have to keep designing cities with giant streets and giant parking lots and traffic lights and traffic lanes and all this infrastructure that takes up so much space and benefits so few people proportionally.”

Note that the Waymos often around empty, just increasing congestion without actually serving anyone:

They’re also moot because 53516F3 doesn’t pick up any passengers: After less than 30 minutes on the road, it turns left into a fenced-in lot across from a budget grocery store. There are no electric-car chargers to be seen, but the lot is teeming with empty Waymos, either parked or pulling in and out, each one with all its lidars still spinning.

…

We settle in to wait for 53516F3 to reemerge. Gabe takes out his ukulele. After about 10 minutes, we decide to abandon our plan to tail a single vehicle.

So we pick a random new robotaxi drone on its way out of the hive: 40757F3. Off we go, running a perfect 25 mph down Bryant Street, passing so close to our office that a coworker who’s tracking our location snaps a picture of us from the window. And after 20 minutes, 40757F3 leads us … straight to another Waymo lot a few blocks from WIRED.

This time we pick up the trail of the first robotaxi to exit: plate 78889X3.

We have high hopes for this one at first, but then we notice it has a yellow “low battery” indicator on its dome. “If it’s going to a lot, I’m going to scream,” WIRED says. Sure enough, 78889X3 takes us 3 miles south to a charging and maintenance lot deep in an industrial zone under an elevated freeway.

…

all this deadheading between parking lots makes us think more about Gabe’s prediction of the urban future. People lament that most cars on the road today are 4,000-pound contraptions with just one person in them. Is Waymo going to make congestion worse by filling the streets with 5,000-pound contraptions that are completely empty?

When we ask Waymo’s chief product officer, Saswat Panigrahi, about all the empty robot-shuffling, he calls it “rebalancing the fleet.” During slow periods, he says, cars will automatically distribute themselves into an ideal position to meet an expected peak demand later on

Yuo, Waymo will only increase congestion:

According to Adam Millard-Ball, an urban planning professor who studies autonomous cars, the past 15 years of Uber and Lyft should offer a decent preview of how robotaxis will affect traffic. (Because with or without a driver, both are private taxi services with a layer of algorithmic efficiency baked in.) And research suggests that in fact Uber and Lyft brought more private cars onto city streets, partly because drivers acquired new ones to gig for the platforms. All that led to—you guessed it—more congestion.

Wired is 100% correct that buses will never be automated due to needing a responsible adult on board:

What about self-driving buses? Waymo says that its “driver” could ultimately be made to pilot trucks, delivery vehicles, large people movers, you name it. The trouble is that it’s hard to save money on labor with self-driving buses; when dozens of lives are at stake in a single vehicle, cities will probably need to keep paying a human minder to supervise robot and passengers alike.

Driverless vehicles are not cost effective:

The logical conclusion may be a world with barely any hired human drivers at all, but for now, high Waymo fares and a short supply of robotaxis are holding off that future. Waymo rides are, anecdotally, slightly more expensive than Lyft or Uber fares with human drivers. According to Panigrahi, this is partly a formula for keeping wait times down; if prices go too low, then too many people try to hail Waymos and end up waiting 25 minutes.

See full article at Wired